4.3.6.2. Effects of Climate Change on River Flows

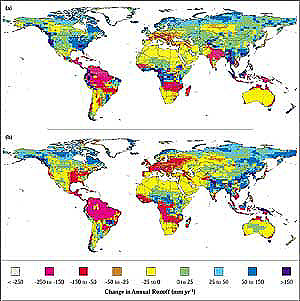

Figure 4-1: Change in average annual runoff by 2050 under HadCM2 ensemble

mean (a) and HadCM3 (b) (Arnell, 1999b). |

By far the majority of studies into the effects of climate

change on river flows have used GCMs to define changes in climate that are applied

to observed climate input data to create perturbed data series. These perturbed

data are then fed through a hydrological model and the resulting changes in

river flows assessed. Since the SAR, there have been several global-scale assessments

and a large number of catchment-scale studies. Confidence in these results is

largely a function of confidence in climate change scenarios at the catchment

scale, although Boorman and Sefton (1997) show that the use of a physically

unrealistic hydrological model could lead to misleading results.

Arnell (1999b) used a macro-scale hydrological model to simulate streamflow

across the world at a spatial resolution of 0.5°x0.5°, under the 1961–1990

baseline climate and under several scenarios derived from HadCM2 and HadCM3

experiments. Figure 4-1 shows the absolute change in annual

runoff by the 2050s under the HadCM2 and HadCM3 scenarios: Both have an increase

in effective CO2 concentrations of 1% yr-1. The patterns

of change are broadly similar to the change in annual precipitation—increases

in high latitudes and many equatorial regions but decreases in mid-latitudes

and some subtropical regions—but the general increase in evaporation means

that some areas that see an increase in precipitation will experience a reduction

in runoff. Alcamo et al. (1997) also simulated the effects of different climate

change scenarios on global river flows, showing broadly similar patterns to

those in Figure 4-1.

Rather than assess each individual study, this section simply tabulates catchment-scale

studies published since the SAR and draws some general conclusions. As in the

SAR, the use of different scenarios hinders quantitative spatial comparisons.

Table 4-2 summarizes the studies published since the SAR,

by continent. All of the studies used a hydrological model to estimate the effects

of climate scenarios, and all used scenarios based on GCM output. The table

does not include sensitivity studies (showing the effects of, for example, increasing

precipitation by 10%) or explore the hydrological implications of past climates.

Although such studies provide extremely valuable insights into the sensitivity

of hydrological systems to changes in climate, they are not assessments of the

potential effects of future global warming.

It is clear from Table 4-2 that there are clear spatial

variations in the numbers and types of studies undertaken to date; relatively

few studies have been published in Africa, Latin America, and southeast Asia.

A general conclusion, consistent across many studies, is that the effects of

a given climate change scenario vary with catchment physical and land-cover

properties and that small headwater streams may be particularly sensitive to

change—as shown in northwestern Ontario, for example, by Schindler et al.

(1996).

|