Figure TS-11: Locations at which systematic long-term studies meet

stringent criteria documenting recent temperature-related regional climate

change impacts on physical and biological systems. Hydrology, glacial retreat,

and sea-ice data represent decadal to century trends. Terrestrial and marine

ecosystem data represent trends of at least 2 decades. Remote-sensing studies

cover large areas. Data are for single or multiple impacts that are consistent

with known mechanisms of physical/biological system responses to observed

regional temperature-related changes. For reported impacts spanning large

areas, a representative location on the map was selected. |

7. Global Issues and Synthesis

7.1. Detection of Climate Change Impacts

Observational evidence indicates that climate changes in the 20th century already

have affected a diverse set of physical and biological systems. Examples of

observed changes with linkages to climate include shrinkage of glaciers; thawing

of permafrost; shifts in ice freeze and break-up dates on rivers and lakes;

increases in rainfall and rainfall intensity in most mid- and high latitudes

of the Northern Hemisphere; lengthening of growing seasons; and earlier flowering

dates of trees, emergence of insects, and egg-laying in birds. Statistically

significant associations between changes in regional climate and observed changes

in physical and biological systems have been documented in freshwater, terrestrial,

and marine environments on all continents. [19.2]

The presence of multiple causal factors (e.g., land-use change, pollution)

makes attribution of many observed impacts to regional climate change a complex

challenge. Nevertheless, studies of systems subjected to significant regional

climate change—and with known sensitivities to that change—find changes

that are consistent with well-established relationships between climate and

physical or biological processes (e.g., shifts in the energy balance of glaciers,

shifts in the ranges of animals and plants when temperatures exceed physiological

thresholds) in about 80% of biological cases and about 99% of physical cases.

Table TS-16 shows ~450 changes in processes or species

that have been associated with regional temperature changes. Figure

TS-11 illustrates locations at which studies have documented regional temperature

change impacts. These consistencies enhance our confidence in the associations

between changes in regional climate and observed changes in physical and biological

systems. Based on observed changes, there is high confidence that 20th century

climate changes have had a discernible impact on many physical and biological

systems. Changes in biota and physical systems observed in the 20th century

indicate that these systems are sensitive to climatic changes that are small

relative to changes that have been projected for the 21st century. High sensitivity

of biological systems to long-term climatic change also is demonstrated by paleorecords.

[19.2.2.]

Signals of regional climate change impacts are expected to be clearer in physical

and biotic systems than in social and economic systems, which are simultaneously

undergoing many complex non-climate-related stresses, such as population growth

and urbanization. Preliminary indications suggest that some social and economic

systems have been affected in part by 20th century regional climate changes

(e.g., increased damages by floods and droughts in some locations, with apparent

increases in insurance impacts). Coincident or alternative explanations for

such observed regional impacts result in only low to medium confidence about

determining whether climate change is affecting these systems. [19.2.2.4]

| Table TS-16: Processes and species found in studies

to be associated with regional temperature change.a |

|

| Region |

Glaciers, Snow Cover/ Melt, Lake/ Stream Iceb

|

Vegetation

|

Invertebrates

|

Amphibians and Reptiles

|

Birds

|

Mammals

|

|

| Africa |

1

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

| Antarctica |

3

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

2

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

| Asia |

14

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

| Australia |

1

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

| Europe |

29

|

4

|

13

|

1

|

46

|

1

|

7

|

0

|

258

|

92

|

7

|

0

|

| North America |

36

|

4

|

32

|

11

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

17

|

4

|

3

|

0

|

| Latin America |

3

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

22

|

0

|

15

|

0

|

—

|

—

|

| Total |

87

|

10

|

47

|

12

|

46

|

1

|

29

|

0

|

292

|

96

|

10

|

0

|

|

7.2. Five Reasons for Concern

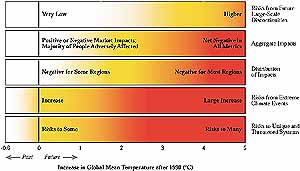

Figure TS-12: Impacts of or risks from climate change, by reason

for concern. Each row corresponds to a reason for concern, and shades correspond

to severity of impact or risk. White means no or virtually neutral impact

or risk, yellow means somewhat negative impacts or low risks, and red means

more negative impacts or higher risks. Global-averaged temperatures in the

20th century increased by 0.6°C and led to some impacts. Impacts are

plotted against increases in global mean temperature after 1990. This figure

addresses only how impacts or risks change as thresholds of increase in

global mean temperature are crossed, not how impacts or risks change at

different rates of change in climate. These temperatures should be taken

as approximate indications of impacts, not as absolute thresholds. |

Some of the current knowledge about climate change impacts,

vulnerability, and adaptation is synthesized here along five reasons for concern:

unique and threatened systems, global aggregate impacts, distribution of impacts,

extreme weather events, and large-scale singular events. Consideration of these

reasons for concern contribute to understanding of vulnerabilities and potential

benefits associated with human-induced climate change that can aid deliberations

by policymakers of what could constitute dangerous interference with the climate

system in the context of Article 2 of the UNFCCC. No single dimension is paramount.

Figure TS-12 presents qualitative findings about climate

change impacts related to the reasons for concern. At a small increase in global

mean temperature,3

some of the reasons for concern show the potential for negative impacts, whereas

others show little adverse impact or risk. At higher temperature increases,

all lines of evidence show a potential for adverse impacts, with impacts in

each reason for concern becoming more negative at increasing temperatures. There

is high confidence in this general relationship between impacts and temperature

change, but confidence generally is low in estimates of temperature change thresholds

at which different categories of impacts would happen. [19.8]

7.2.1. Unique and Threatened Systems

Small increases in global average temperature may cause significant and irreversible

damage to some systems and species, including possible local, regional, or global

loss. Some plant and animal species, natural systems, and human settlements

are highly sensitive to climate and are likely to be adversely affected by climate

changes associated with scenarios of <1°C mean global warming. Adverse

impacts to species and systems would become more numerous and more serious for

climatic changes that would accompany a global mean warming of 1-2°C and

are highly likely to become even more numerous and serious at higher temperatures.

The greater the rate and magnitude of temperature and other climatic changes,

the greater the likelihood that critical thresholds of systems would be surpassed.

Many of these threatened systems are at risk from climate change because they

face nonclimate pressures such as those related to human land use, land-use

change, and pollution. [19.3]

Species that may be threatened with local or global extinction by changes in

climate that may accompany a small mean global temperature increase include

critically endangered species generally, species with small ranges and low population

densities, species with restricted habitat requirements, and species for which

suitable habitat is patchy in distribution, particularly if under pressure from

human land-use and land-cover change. Examples of species that may be threatened

by small changes include forest birds in Tanzania, the Resplendent Quetzal in

Central America, the mountain gorilla in Africa, amphibians that are endemic

to cloud forests of the neotropics, the spectacled bear of the Andes, the Bengal

tiger and other species that are endemic to the Sundarban wetlands, and rainfall-sensitive

plant species that are endemic to the Cape Floral Kingdom of South Africa. Natural

systems that may be threatened include coral reefs, mangroves, and other coastal

wetlands; montane ecosystems that are restricted to the upper 200-300 m of mountainous

areas; prairie wetlands; remnant native grasslands; coldwater and some coolwater

fish habitat; ecosystems overlying permafrost; and ice edge ecosystems that

provide habitat for polar bears and penguins. Human settlements that may be

placed at serious risk by changes in climate and sea level that may be associated

with medium to large mean warming include some settlements of low-lying coastal

areas and islands, floodplains, and hillsides—particularly those of low

socioeconomic status such as squatter and other informal settlements. Other

potentially threatened settlements include traditional peoples that are highly

dependent on natural resources that are sensitive to climate change. [19.3]

|