20.3 Impacts and adaptation in the context of multiple stresses

20.3.1 A catalogue of multiple stresses

The current literature shows a growing appreciation of the multiple stresses that ecological and socio-economic systems face, how those stresses are likely to change over the next several decades, and what some of the net environmental consequences are likely to be. The Pilot Analysis of Global Ecosystems prepared by the World Resources Institute (WRI, 2000) conducted literature reviews to document the state and condition of forests, agro-ecosystems, freshwater ecosystems and marine systems. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) comprehensively documented the condition and recent trends of ecosystems, the services they provide and the socio-economic context within which they occur. It also provided several scenarios of possible future conditions (MA, 2005). For reference, the MA offered some startling statistics. Cultivated systems covered 25% of Earth’s terrestrial surface in 2000. On the way to achieving this coverage, global agricultural enterprises converted more area to cropland between 1950 and 1980 than in the 150 years between 1700 and 1850. As of the year 2000, 35% of the world’s mangrove areas and 20% of the world’s coral reefs had been lost (with another 20% having been degraded significantly). Since 1960, withdrawals from rivers and lakes have doubled, flows of biologically available nitrogen in terrestrial ecosystems have doubled, and flows of phosphorus have tripled. At least 25% of major marine fish stocks have been overfished and global fish yields have actually begun to decline. MA (2005) identified major changes in land cover, the consequences of which were explored by Foley et al. (2005).

The MA (2005) recognised two different categories of drivers of change. Direct drivers of ecosystem change affect ecosystem characteristics in specific, quantifiable ways; examples include land-cover and land-use change, climate change and species introductions. Indirect drivers affect ecosystems in a more diffuse way, generally by affecting one or more direct drivers; here examples are demographic changes, socio-political changes and economic changes. Both types of drivers have changed substantially in the past few decades and will continue to do so. Among direct drivers, for example, over the past four decades, food production has increased by 150%, water use has doubled, wood harvests for pulp and paper have tripled, timber production has doubled and installed hydropower capacity has doubled. On the indirect side, global population has doubled since the 1960s to reach 6 billion people while the global economy has increased more than six fold.

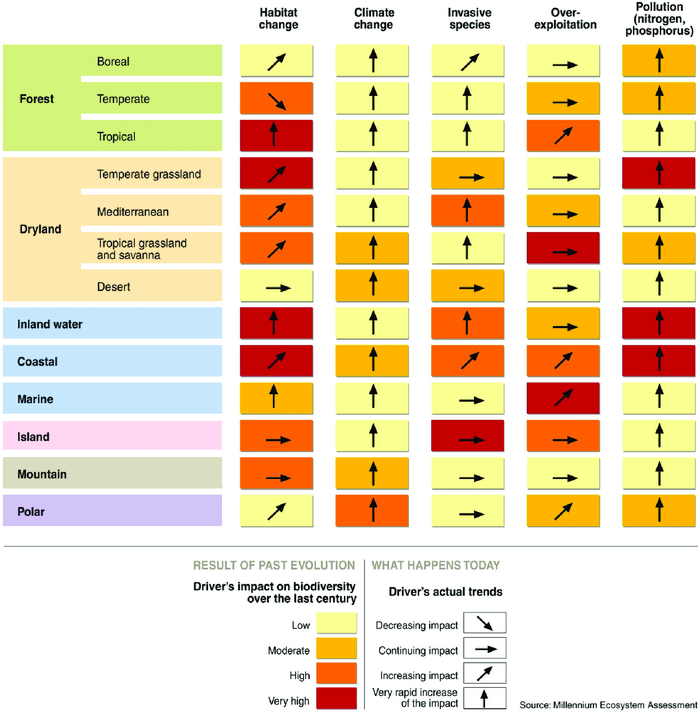

Table 20.1 documents expectations for how several of the direct drivers of ecosystem change are likely to change in magnitude and importance over time. With the exception of polar regions, coastal ecosystems, some dryland systems and montane regions, climate change is not, today, a major source of stress; but climate change is the only direct driver whose magnitude and importance to a series of regions, ecosystems and resources is likely to continue to grow over the next several decades. Table 20.1 illustrates the degree to which these ecosystems are currently experiencing stresses from several direct drivers of change simultaneously. It shows that potential interactions with climate change are likely to grow over the next few decades with the magnitude of climate change itself.

Table 20.1. Drivers of change in ecosystem services. Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA, 2005).