|

4. SRES Writing Team, Approach, and Process

IPCC Working Group III (WGIII) appointed the SRES writing team in January 1997.

After some adjustments, it eventually came to include more than 50 members from

18 countries. Together they represent a broad range of scientific disciplines,

regional backgrounds, and non-governmental organizations. In particular, the

team includes representatives of six scenario modeling groups and a number of

lead authors from all three earlier IPCC scenario activities: the 1990 and 1992

scenarios and the 1995 scenario evaluation. Their expertise and familiarity

with earlier IPCC emissions scenario work assured continuity and allowed the

SRES effort to build efficiently upon prior work. The SRES team worked in close

collaboration with colleagues on the IPCC Task Group on Climate Scenarios for

Impact Assessment (TGCIA) and with colleagues from all three IPCC Working Groups

(WGs) of the Third Assessment Report (TAR). Appendix II lists the members of

the writing team and their affiliations and Chapter 1 gives a more detailed

description of the SRES approach and process.

Taking the above audiences and purposes into account, the following more precise

specifications for the new SRES scenarios were developed. The new scenarios

should:

- cover the full range of radiatively important gases, which include direct

and indirect GHGs and SO2 ;

- have sufficient spatial resolution to allow regional assessments of climate

change in the global context;

- cover a wide spectrum of alternative futures to reflect relevant uncertainties

and knowledge gaps;

- use a variety of models to reflect methodological pluralism and uncertainty;

- incorporate input from a wide range of scientific disciplines and expertise

from non-academic sources through an open process;

- exclude additional initiatives and policies specifically designed to reduce

climate change;

- cover and describe to the extent possible a range of policies that could

affect climate change although they are targeted at other issues, for example,

reductions in SO2 emissions to limit acid rain;

- cover as much as possible of the range of major underlying driving forces

of emission scenarios identified in the open literature;

- be transparent with input assumptions, modeling approaches, and results

open to external review;

- be reproducible - document data and methodology adequately enough to allow

other researchers to reproduce the scenarios; and

- be internally consistent - the various input assumptions and data of the

scenarios are internally consistent to the extent possible.

The writing team agreed that the scenario formulation process would consist

of five major components:

- review of existing scenarios in the literature;

- analysis of their main characteristics and driving forces;

- formulation of narrative "storylines" to describe alternative futures;

- quantification of storylines with different modeling approaches; and

- "open" review process of emissions scenarios and their assumptions

As is evident from the components of the work program, there was agreement

that the process be an open one with no single "official" model and no exclusive

"expert teams." In 1997 the IPCC advertised in a number of relevant scientific

journals and other publications to solicit wide participation in the process.

To facilitate participation and improve the usefulness of the new scenarios,

the SRES web site (http://sres.ciesin.org/)

was created. In addition, members of the writing team published much of the

background work used for formulating SRES scenarios in the peer-reviewed literature

3

and on web sites (see Appendix IV). Finally, the revised

set of scenarios, the web sites, and the draft of this report have been evaluated

through the IPCC expert and government review processes. This process resulted

in numerous changes and revisions of the report. In particular, during the approval

process of the Summary for Policymakers (SPM) in March 2000 at the 5th Session

of the WG III in Katmandu changes in this SPM were agreed that necessitated

some changes in the underlying document, including this Technical Summary. These

changes have been implemented in agreement with the Lead Authors.

5. Scenario Literature Review and Analysis

The first step in the formulation of the SRES scenarios was the review and

the analysis of the published literature and the development of the database

with more than 400 emissions scenarios that is accessible through the web site

(www-cger.nies.go.jp/cger-e/db/ipcc.html);

190 of these extend to 2100 and are considered in the comparison with the SRES

scenarios in the subsequent Figures. Chapters 2 and 3 give a more detailed description

of the literature review and analysis.

|

(click to enlarge)

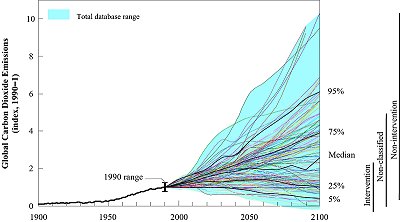

Figure TS-1: Global energy-related

and industrial CO2 emissions - historical development and future scenarios,

shown as an index (1990 = 1). The median (50th), the 5th, and 95th percentiles of the frequency distribution are also shown. The statistics

associated with scenarios from the literature do not imply probability

of occurrence (e.g., the frequency distribution of the scenarios may

be influenced by the use of IS92a as a reference for many subsequent

studies). The emissions paths indicate a wide range of future emissions.

The range is also large in the base year 1990 and is indicated by an

"error" bar. To separate the variation due to base-year specification

from different future paths, emissions are indexed for the year 1990,

when actual global energy-related and industrial CO2 emissions were

about 6 GtC. The coverage of CO2 emissions sources may vary across the

256 different scenarios from the database included in the figure. The

scenario samples used vary across the time steps (for 1990 256 scenarios,

for 2020 and 2030 247, for 2050 211, and for 2100 190 scenarios). Also

shown, as vertical bars on the right of the figure, are the ranges of

emissions in 2100 of IS92 scenarios and for scenarios from the literature

that apparently include additional climate initiatives (designated as

"intervention" scenarios emissions range), those that do not ("non-intervention"),

and those that cannot be assigned to either of these two categories

("non-classified"). This classification is based on the subjective evaluation

of the scenarios in the database by the members of the writing team

and is explained in Chapter 2. Data sources: Morita

and Lee, 1998a, 1998b; Nakic´enovic´ et al., 1998.

|

Figure TS-1 shows the global energy-related and industrial

CO2 emission paths from the database as "spaghetti" curves for the period to

2100 against the background of the historical emissions from 1900 to 1990. These

curves are plotted against an index on the vertical axis rather than as absolute

values because of the large differences and discrepancies for the values assumed

for the base year 1990. These sometimes arise from genuine differences among

the scenarios (e.g., different data sources, definitions) and sometimes from

different base years assumed in the analysis or from alternative calibrations.4

The differences among the scenarios in the specification of the base year illustrate

the large genuine scientific and data uncertainty that surrounds emissions and

their main driving forces captured in the scenarios. The literature includes

scenarios with additional climate polices, which are sometimes referred to as

mitigation or intervention scenarios.

There are many ambiguities associated with the classification of emissions

scenarios into those that include additional climate initiatives and those that

do not. Many cannot be classified in this way on the basis of the information

available from the database. Figure TS-1 indicates the

ranges of emissions in 2100 from scenarios that apparently include additional

climate initiatives (designated as "intervention" emissions range), those that

do not ("non-intervention") and those that cannot be assigned to either of these

two categories ("non-classified"). This classification is based on the subjective

evaluation of the scenarios in the database by the members of the writing team

and is explained in Chapter 2. The range of the whole sample of scenarios has

significant overlap with the range of those that cannot be classified and they

share virtually the same median (15.7 and 15.2 GtC in 2100, respectively), but

the non-classified scenarios do not cover the high part of the range. Also,

the range of the scenarios that apparently do not include climate polices (non-intervention)

has considerable overlap with the other two ranges (the lower bound of non-intervention

scenarios is higher than the lower bounds of the intervention and non-classified

scenarios), but with a significantly higher median (of 21.3 GtC in 2100).

Historically, gross anthropogenic CO2 emissions have increased at an average

rate of about 1.7% per year since 1900 (Nakicenovic et al., 1996);

if that historical trend continues global emissions would double during the

next three to four decades and increase more than sixfold by 2100. Many scenarios

in the database describe such a development. However, the range is very large

around this historical trend so that the highest scenarios envisage about a

tenfold increase of global emissions by 2100 as compared with 1990, while the

lowest have emissions lower than today. The median and the average of the scenarios

lead to about a threefold emissions increase over the same time period or to

about 16 GtC by 2100. This is lower than the median of the IS92 set and is lower

than the IS92a scenario, often considered as the "central" scenario with respect

to some of its tendencies. However, the distribution of emissions is asymmetric.

The thin emissions "tail" that extends above the 95th percentile (i.e., between

the six- and tenfold increase of emissions by 2100 compared to 1990) includes

only a few scenarios. The range of other emissions and the main scenario driving

forces (such as population growth, economic development and energy production,

conversion and end use) for the scenarios documented in the database is also

large and comparable to the variation of CO2 emissions. Statistics associated

with scenarios from the literature do not imply probability of occurrence or

likelihood of the scenarios. The frequency distribution of the database may

be influenced by the use of IS92a as a reference for scenario studies and by

the fact that many scenarios in the database share common assumptions prescribed

for the purpose of model comparisons with similar scenario driving forces.

One of the recommendations of the writing team is that IPCC or a similar international

institution should maintain such a database thereby ensuring continuity of knowledge

and scientific progress in any future assessments of GHG scenarios. An equivalent

database for documenting narrative and other qualitative scenarios is considered

to be also very useful for future climate-change assessments. One difficulty

encountered in the analysis of the emissions scenarios is that the distinction

between climate policies and non-climate policy scenarios and other scenarios

appeared to be to a degree arbitrary and often impossible to make. Therefore,

the writing team recommends that an effort should be made in the future to develop

an appropriate emissions scenario classification scheme.

|