|

| Question 2

What is the evidence for, causes of, and consequences

of changes in the Earth's climate since the pre-industrial era?

- Has the Earth's climate changed since the pre-industrial

era at the regional and/or global scale? If so, what part, if any, of

the observed changes can be attributed to human influence and what part,

if any, can be attributed to natural phenomena? What is the basis for

that attribution?

- What is known about the environmental, social, and

economic consequences of climate changes since the pre-industrial era

with an emphasis on the last 50 years?

|

|

|

| |

|

| The Earth's climate system has demonstrably

changed on both global and regional scales since the pre-industrial era,

with some of these changes attributable to human activities. |

Q2.2

Q2.2

|

| |

|

| Human activities have increased the atmospheric

concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols since the pre-industrial

era. The atmospheric concentrations of key anthropogenic greenhouse

gases (i.e., carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4),

nitrous oxide (N2O), and tropospheric ozone (O3))

reached their highest recorded levels in the 1990s, primarily due to the

combustion of fossil fuels, agriculture, and land-use changes (see Table

SPM-1). The radiative forcing from anthropogenic greenhouse gases

is positive with a small uncertainty range; that from the direct aerosol

effects is negative and smaller; whereas the negative forcing from the

indirect effects of aerosols on clouds might be large but is not well

quantified.

|

Q2.4-5

Q2.4-5

|

| An increasing body of observations gives a collective picture

of a warming world and other changes in the climate system (see Table

SPM-1). |

Q2.6

Q2.6 |

| |

|

| Globally it is very likely that the 1990s was the

warmest decade, and 1998 the warmest year, in the instrumental record (1861-2000)

(see Box SPM-1). The

increase in surface temperature over the 20th century for the Northern Hemisphere

is likely to have been greater than that for any other century in the last

thousand years (see Table SPM-1).

Insufficient data are available prior to the year 1860 in the Southern Hemisphere

to compare the recent warming with changes over the last 1,000 years. Temperature

changes have not been uniform globally but have varied over regions and

different parts of the lower atmosphere. |

Q2.7

Q2.7 |

| |

|

| Table SPM-1:

20th century changes in the Earth's atmosphere, climate, and

biophysical system.a |

| Indicator |

Observed Changes |

| Concentration

indicators |

|

| Atmospheric concentration of CO2 |

280 ppm for the period 1000-1750 to 368 ppm in year

2000 (31±4% increase). |

| Terrestrial biospheric CO2 exchange |

Cumulative source of about 30 Gt C between the years

1800 and 2000; but during the 1990s, a net sink of about 14±7

Gt C. |

| Atmospheric concentration of CH4 |

700 ppb for the period 1000-1750 to 1,750 ppb in year

2000 (151±25% increase). |

| Atmospheric concentration of N2O |

270 ppb for the period 1000-1750 to 316 ppb in year

2000 (17±5% increase). |

| Tropospheric concentration of O3 |

Increased by 35±15% from the years 1750 to

2000, varies with region. |

| Stratospheric concentration of O3 |

Decreased over the years 1970 to 2000, varies with

altitude and latitude. |

| Atmospheric concentrations of HFCs, PFCs, and SF6 |

Increased globally over the last 50 years. |

| Weather indicators |

|

| Global mean surface temperature |

Increased by 0.6±0.2°C over the 20th century;

land areas warmed more than the oceans (very likely). |

Northern Hemisphere surface

temperature |

Increased over the 20th century greater than during

any other century in the last 1,000 years; 1990s warmest decade of

the millennium (likely). |

| Diurnal surface temperature range |

Decreased over the years 1950 to 2000 over land: nighttime

minimum temperatures increased at twice the rate of daytime maximum

temperatures (likely). |

| Hot days / heat index |

Increased (likely). |

| Cold / frost days |

Decreased for nearly all land areas during the 20th

century (very likely). |

| Continental precipitation |

Increased by 5-10% over the 20th century in the Northern

Hemisphere (very likely), although decreased in some regions

(e.g., north and west Africa and parts of the Mediterranean). |

| Heavy precipitation events |

Increased at mid- and high northern latitudes (likely). |

| Frequency and severity of drought |

Increased summer drying and associated incidence of

drought in a few areas (likely). In some regions, such as

parts of Asia and Africa, the frequency and intensity of droughts

have been observed to increase in recent decades. |

| Biological and physical

indicators |

|

| Global mean sea level |

Increased at an average annual rate of 1 to 2 mm during

the 20th century. |

| Duration of ice cover of rivers and lakes |

Decreased by about 2 weeks over the 20th century in

mid- and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (very likely). |

| Arctic sea-ice extent and thickness |

Thinned by 40% in recent decades in late summer to

early autumn (likely) and decreased in extent by 10-15% since

the 1950s in spring and summer. |

| Non-polar glaciers |

Widespread retreat during the 20th century. |

| Snow cover |

Decreased in area by 10% since global observations

became available from satellites in the 1960s (very likely). |

| Permafrost |

Thawed, warmed, and degraded in parts of the polar,

sub-polar, and mountainous regions. |

| El Niño events |

Became more frequent, persistent, and intense during

the last 20 to 30 years compared to the previous 100 years. |

| Growing season |

Lengthened by about 1 to 4 days per decade during

the last 40 years in the Northern Hemisphere, especially at higher

latitudes. |

| Plant and animal ranges |

Shifted poleward and up in elevation for plants, insects,

birds, and fish. |

| Breeding, flowering, and migration |

Earlier plant flowering, earlier bird arrival, earlier

dates of breeding season, and earlier emergence of insects in the

Northern Hemisphere. |

| Coral reef bleaching |

Increased frequency, especially during El Niño

events. |

| Economic indicators |

|

| Weather-related economic losses |

Global inflation-adjusted losses rose an order of

magnitude over the last 40 years (see Q2 Figure

2-7). Part of the observed upward trend is linked to socio-economic

factors and part is linked to climatic factors. |

| a. This table provides

examples of key observed changes and is not an exhaustive list. It

includes both changes attributable to anthropogenic climate change

and those that may be caused by natural variations or anthropogenic

climate change. Confidence levels are reported where they are explicitly

assessed by the relevant Working Group. An identical table in the

Synthesis Report contains cross-references to the WGI and WGII reports. |

| Box SPM-1: Confidence and likelihood

statements. |

| Where appropriate, the authors of

the Third Assessment Report assigned confidence levels that represent

their collective judgment in the validity of a conclusion based

on observational evidence, modeling results, and theory that they

have examined. The following words have been used throughout the

text of the Synthesis Report to the TAR relating to WGI findings:

virtually certain (greater than 99% chance that a result

is true); very likely (90-99% chance); likely

(66-90% chance); medium likelihood (33-66% chance);

unlikely (10-33% chance); very unlikely (1-10%

chance); and exceptionally unlikely (less than 1% chance).

An explicit uncertainty range (±) is a likely range.

Estimates of confidence relating to WGII findings are: very

high (95% or greater), high (67-95%), medium

(33-67%), low (5-33%), and very low

(5% or less). No confidence levels were assigned in WGIII. |

|

|

| |

|

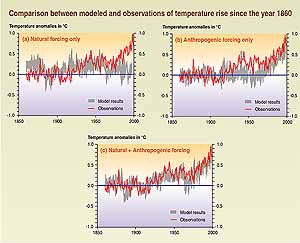

| There is new and stronger evidence that most of the

warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities.

Detection and attribution studies consistently find evidence for an anthropogenic

signal in the climate record of the last 35 to 50 years. These studies include

uncertainties in forcing due to anthropogenic sulfate aerosols and natural

factors (volcanoes and solar irradiance), but do not account for the effects

of other types of anthropogenic aerosols and land-use changes. The sulfate

and natural forcings are negative over this period and cannot explain the

warming; whereas most of these studies find that, over the last 50 years,

the estimated rate and magnitude of warming due to increasing greenhouse

gases alone are comparable with, or larger than, the observed warming. The

best agreement between model simulations and observations over the last

140 years has been found when all the above anthropogenic and natural forcing

factors are combined, as shown in Figure

SPM-2. |

Q2.9-11

Q2.9-11 |

| |

|

| Changes in sea level, snow cover, ice extent, and

precipitation are consistent with a warming climate near the Earth's

surface. Examples of these include a more active hydrological cycle

with more heavy precipitation events and shifts in precipitation, widespread

retreat of non-polar glaciers, increases in sea level and ocean-heat content,

and decreases in snow cover and sea-ice extent and thickness (see Table

SPM-1). For instance, it is very likely that the 20th century warming

has contributed significantly to the observed sea-level rise, through thermal

expansion of seawater and widespread loss of land ice. Within present uncertainties,

observations and models are both consistent with a lack of significant acceleration

of sea-level rise during the 20th century. There are no demonstrated changes

in overall Antarctic sea-ice extent from the years 1978 to 2000. In addition,

there are conflicting analyses and insufficient data to assess changes in

intensities of tropical and extra-tropical cyclones and severe local storm

activity in the mid-latitudes. Some of the observed changes are regional

and some may be due to internal climate variations, natural forcings, or

regional human activities rather than attributed solely to global human

influence. |

Q2.12-19

Q2.12-19 |

| |

|

| Observed changes in regional climate

have affected many physical and biological systems, and there are preliminary

indications that social and economic systems have been affected.

Figure

SPM-2: Simulating the Earth's temperature variations (°C)

and comparing the results to the measured changes can provide insight

to the underlying causes of the major changes. A climate

model can be used to simulate the temperature changes that occur from

both natural and anthropogenic causes. The simulations represented

by the band in (a) were done with only natural forcings: solar variation

and volcanic activity. Those encompassed by the band in (b) were done

with anthropogenic forcings: greenhouse gases and an estimate of sulfate

aerosols. And those encompassed by the band in (c) were done with

both natural and anthropogenic forcings included. From (b), it can

be seen that the inclusion of anthropogenic forcings provides a plausible

explanation for a substantial part of the observed temperature changes

over the past century, but the best match with observations is obtained

in (c) when both natural and anthropogenic factors are included. These

results show that the forcings included are sufficient to explain

the observed changes, but do not exclude the possibility that other

forcings may also have contributed. Figure

SPM-2: Simulating the Earth's temperature variations (°C)

and comparing the results to the measured changes can provide insight

to the underlying causes of the major changes. A climate

model can be used to simulate the temperature changes that occur from

both natural and anthropogenic causes. The simulations represented

by the band in (a) were done with only natural forcings: solar variation

and volcanic activity. Those encompassed by the band in (b) were done

with anthropogenic forcings: greenhouse gases and an estimate of sulfate

aerosols. And those encompassed by the band in (c) were done with

both natural and anthropogenic forcings included. From (b), it can

be seen that the inclusion of anthropogenic forcings provides a plausible

explanation for a substantial part of the observed temperature changes

over the past century, but the best match with observations is obtained

in (c) when both natural and anthropogenic factors are included. These

results show that the forcings included are sufficient to explain

the observed changes, but do not exclude the possibility that other

forcings may also have contributed. |

|

Q2.20

& Q2.25 Q2.20

& Q2.25 |

Q2 Figure 2-4

Q2 Figure 2-4 |

| |

|

| Recent regional changes in climate, particularly increases

in temperature, have already affected hydrological systems and terrestrial

and marine ecosystems in many parts of the world (see Table

SPM-1). The observed changes

in these systems1

are coherent across diverse localities and/or regions and are consistent

in direction with the expected effects of regional changes in temperature.

The probability that the observed changes in the expected direction (with

no reference to magnitude) could occur by chance alone is negligible. |

Q2.21-24

Q2.21-24 |

| |

|

| The rising socio-economic costs related to weather

damage and to regional variations in climate suggest increasing vulnerability

to climate change. Preliminary indications suggest that some social

and economic systems have been affected by recent increases in floods and

droughts, with increases in economic losses for catastrophic weather events.

However, because these systems are also affected by changes in socio-economic

factors such as demographic shifts and land-use changes, quantifying the

relative impact of climate change (either anthropogenic or natural) and

socio-economic factors is difficult. |

Q2.25-26

Q2.25-26 |

|

|