|

4.2.3. Model Results for Subsonic Aircraft Emissions

4.2.3.1. Ozone Perturbation

|

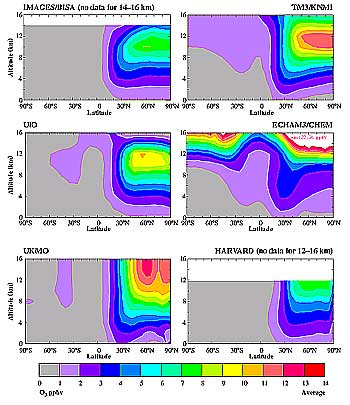

Figure 4-1: Annual (2015) and zonal average increases of ozone

volume mixing ratios [ppbv] from aircraft emissions calculated by six

3-D models. The IMAGES/BISA model does not give results above 14 km, and

the HARVARD model does not give results above 12 km.

|

|

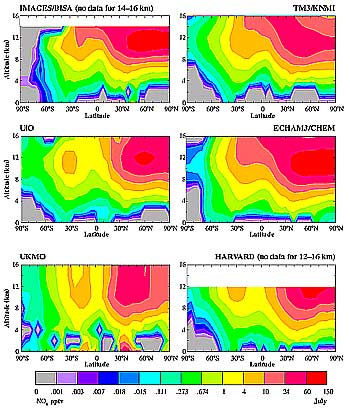

Figure 4-2: July zonal average increase in NOx [pptv]

from aircraft.

|

Figure 4-1 presents annual zonal average increases

of O3 volume mixing ratios caused by aircraft

NOx emissions predicted by the six models for

the year 2015. As this figure shows, the models treat the tropopause significantly

differently, which leads to qualitatively different O3

distributions and calculated O3 perturbations

near the tropopause. The UiO model calculates a maximum increase of O3

of about 9 ppbv around 40-80°N at an elevation of 10-13 km. Throughout most

of the Northern Hemisphere, increases larger than 1 ppbv are calculated. The

IMAGES/BISA and HARVARD models calculate somewhat smaller peak perturbations

of about 7 ppbv. In contrast, the Tm3/KNMI and the UKMO models calculate

maximum changes of about 11 ppbv. The UKMO model computes large increases up

to the 16-km level, probably as a result of relatively large vertical exchange

rates in the vicinity of the tropopause. In contrast to the other models, the

ECHAm3/CHEM model predicts the highest O3

perturbations in the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere LS. Tropospheric

changes are smaller than in the other models, however. The difference may be

partly a result of the length of the ECHAm3/CHEM model run. This

model has a representation of the stratosphere and reported results from the

average of the last 10 years of a 15-year simulation-long enough to propagate

aircraft emissions and O3 perturbation in the

Northern Hemisphere to the Southern Hemisphere (via the stratosphere). The other

3-D models do not account for such stratospheric transport processes because

they constrain O3 concentrations in their upper

model levels: They fix their upper model layer concentrations using observations,

or they prescribe O3 fluxes from the stratosphere

into the troposphere. The use of these boundary conditions could lead to a calculated

impact on stratospheric O3 that is too small.

It may also be that the ECHAm3/CHEM model has too efficient transport

in the LS.

The effect of constraining concentrations and fluxes at the upper boundary

of the 3-D models was checked by running the stratospheric 2-D Atmospheric and

Environmental Research, Inc. (AER) model for the same subsonic scenario. Consistent

with the 3-D models, the AER model calculates a maximum O3

increase of 8-10 ppbv in the Northern Hemisphere at an altitude of 8-12 km.

In the stratosphere at 16 km, small increases of 2 ppbv in the Southern Hemisphere

and 6 ppbv in the Northern Hemisphere are calculated-somewhat higher, but consistent

with most 3-D models. Calculated O3 increases

are strongest in the UT and the LS. In the lower troposphere (< 6 km), the increase

is reduced by a factor of about 5 in mixing ratio compared to the UT. All models

calculate that about 85% of the O3 increase for

1992 is in the Northern Hemisphere; for 2015 and 2050, the portions are about

80 and 75%, respectively.

Although emissions of precursor NOx are spatially

distributed heterogeneously, the resulting O3

increases are distributed more uniformly as a result of the combined effects

of strong longitudinal mixing and the relatively long residence time of O3

in the free troposphere and LS. All models show efficient transport of excess

O3 from source regions at mid-latitudes to high

latitudes, where the residence time of O3 is

particularly long as a result of decreased deposition (Stevenson et al., 1997;

Wauben et al., 1997; Berntsen and Isaksen, 1999).

There may be a strong seasonal cycle in the calculated impact of aircraft emissions

on O3. For example, using the same emission scenarios,

the UiO and the UKMO models calculate a 40% larger increase of O3

in the Northern Hemisphere in April compared to July (Stevenson et al., 1997;

Berntsen and Isaksen, 1999). Other models find much weaker seasonal cycles (e.g.,

IMAGES/BISA and ECHAm3/CHEM), or find maximum increases in summer

(e.g., Tm3/KNMI and HARVARD). These seasonal differences are probably

associated with different background NOx conditions

in the different models (see Section 4.2.3.2).

4.2.3.2. NOx Perturbation

Figure 4-2 shows calculated zonal average increases

of NOx from aircraft emissions in July 2015.

In the Northern Hemisphere, all but one model calculate increases of up to 150

pptv. These increases can be compared with background levels of 50-200 pptv

at northern mid-latitudes in the 12-km region. In the stratosphere, the ECHAm3/CHEM

model calculates larger increases, probably as a result of more efficient transport

to the stratosphere. The height distribution of NOx

increases is very similar among models. All models also predict noticeable increases

in upper tropospheric NOx at low latitudes in

the Southern Hemisphere. Only small increases are estimated in the lower troposphere.

Background NOx conditions, however, are rather

different in the 3-D CTMs. For instance, at 12 km at 50°N, calculated background

NOx mixing ratios may vary, depending on the

season, by a factor of 2 to 4. Such large differences could be important for

O3 production because of the nonlinear dependency

of net O3 production on NOx

concentrations, although, for the model scenarios explored, the global O3

increase appears to be almost linear for most of the anticipated NOx

injections in the models (see Figure 4-3).

4.2.3.3. Future Total Ozone Increases from Aircraft

Emissions and Comparison with Increases from Other Sources

|

Figure 4-3: Increase in annual average global O3 abundance

(Tg O3) up to 16 km from present and future aircraft emissions.

|

Figure 4-3 presents the increase of global O3

abundance up to 16 km from aircraft emissions. The annual emissions of 0.5,

1.27, and 2.17 Tg N correspond to (projected) emissions for 1992, 2015, and

2050, respectively. Calculated O3 increases range

from 4 to 7 Tg in 1992, 9 to 17 Tg in 2015, and 19 to 24 Tg in 2050. For each

CTM, the global O3 increase scales almost linearly

with aircraft NOx emissions-even for the 2050

high-demand sensitivity study G (3.46 Tg N yr-1). However, O3

production is less efficient at high NOx emissions.

The nearly linear response of global O3 increase

to aircraft NOx emissions was not anticipated,

given the well-known nonlinear O3 production

as a function of NOx (discussed in Chapter

2). The main explanation seems to be that aircraft NOx

and associated reservoir species (e.g., HNO3)

are transported out of aircraft corridors, where net O3

production depends more linearly on NOx. We should

recognize, however, that all of the global models used in this study have a

coarse resolution that may systematically overestimate the O3

production. Secondary effects are background increases in CH4

and CO (as a result of enhanced surface emissions in 2015 and 2050), leading

to somewhat more efficient O3 production per

NOx molecule emitted, and the shift of emissions

from Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes toward the tropics, where background

NOx concentrations are smaller.

To further test linearity in O3 increases to

NOx emission beyond the upper limit selected

in these model studies, an extremely high NOx

emission of 1.5 times the high-demand, low-technology case (Scenario G) was

run with the UiO model. This scenario showed only slight nonlinearity at lower

NOx emissions. This extreme simulation indicated

that a level of nonlinearity was reached at northern latitudes where O3

increases of only 10% were obtained, whereas at southern latitudes, where emissions

are smaller, O3 increases (approximately 50%)

were nearly linear with increases in NOx emissions.

Figure 4-4 shows the global increases of total O3

from aircraft emissions in 2015 and 2050 relative to those in 1992-that is,

the difference of O3 budgets for scenarios listed

in Table 4-4 (D with respect to B and F with respect

to B). The same figure also shows the increases of O3

in 2015 and 2050 from the effects of changes in surface emissions (Section

4.2.2.1)-that is, the differences for scenarios C with respect to A and

E with respect to A. Aircraft emissions account for approximately 15-30% of

the total O3 increase in 2015 and 15-20% in 2050.

It should be noted, however, that the projections of aircraft emissions and

the IPCC IS92a scenario underlying the increase of surface emissions are extremely

uncertain. Changes in aircraft or surface emissions scenarios could change the

relative contribution from aircraft emissions to O3

perturbations significantly. Using scenario G (high demand), an approximately

45% higher increase of O3 from aircraft is calculated

in 2050 by the UiO model (see sensitivity studies).

4.2.3.4. Influence of Changing OH on CH4

Lifetime

|

Figure 4-4: Increases in global total tropospheric ozone abundances

(Tg O3) in 2015 and 2050 from aircraft and other anthropogenic (industrial)

emissions relative to 1992.

|

As discussed in Section 2.1.4, aircraft NOx

emissions lead to higher OH concentrations. In the troposphere, CH4

is removed mainly by reaction with the OH radical. Therefore, a higher OH concentration

will lead to more rapid removal of CH4 from the

atmosphere. Table 4-5 presents the chemical lifetime

of CH4 and changes from aircraft emissions for

scenarios A-F. The lifetime in Table 4-5 is defined

as the CH4 amount up to 300 hPa divided by the

amount annually destroyed by chemical processes. There are large differences

in CH4 lifetimes calculated by the models for

base cases A, C, and E. It is beyond the scope of this report to assess what

causes these differences, but it can be generally said that global OH is very

sensitive to photolysis rates, parameterization of lightning NOx

emissions, and the amount and distribution of surface NOx

and other emissions. Comparing simulations A, C, and E, which show enhancements

from changes in surface emissions, CH4 lifetimes

increase by 0.5-3.2% from 1992 to 2015 and by 7-12% from 1992 to 2050. The decrease

of OH concentrations is a result of the strong effect of anthropogenic CO emissions

and higher background CH4 concentrations, which

dominate the effect of surface emissions of NOx.

The models are rather consistent in their estimates of changes of CH4

lifetimes from aircraft emissions. Comparing simulations with and without aircraft

emissions, CH4 lifetimes are calculated to decrease

globally by 1.2-1.5% in 1992, 1.6-2.9% in 2015, and 2.3-4.3% in 2050.

Changes in calculated CH4 lifetime from aircraft

emissions for the three time periods considered are surprisingly similar in

the model studies. With the exception of the ECHAm3/CHEM model, which

gives smaller perturbations than the other models because it uses a fixed mixing

ratio boundary condition for CO, the differences among models for aircraft impacts

are within 20%. This perturbation of CH4 residence

time from aircraft emissions is significantly larger than that obtained in previous

studies (IPCC, 1995; Fuglestvedt et al., 1996) using 2-D models. CH4

loss is dominated by OH changes in the tropical and subtropical regions of the

lower troposphere. These previous studies showed OH changes that were largely

restricted to the UT, where OH perturbations have little impact on CH4

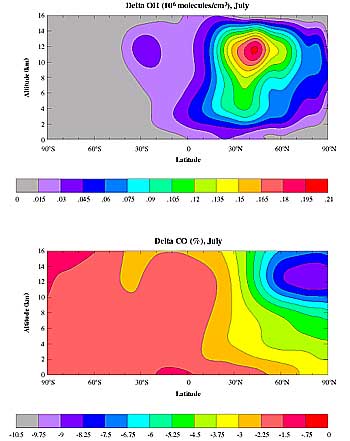

residence time. Figure 4-5a shows the perturbation

in the zonally averaged OH field (July) for 2015 aircraft emissions (given in

106 molecules/cm-3) from the UiO model. The figure shows that the

perturbations extend well into the lower troposphere at most latitudes in the

Northern Hemisphere. One explanation for this result could be that CO, which

accounts for most of the OH loss, has a sufficiently long lifetime to be transported

over large distances. The impact on CO in one region could influence CO (Figure

4-5b) and OH in other regions (e.g., low-latitude lower troposphere), leading

to the estimated impact on CH4. Similar CO changes

were found, for example, in the Tm3/ KNMI model. In addition to changes

in CO, relatively small O3 changes are predicted

in the warm humid tropics. These changes also lead to somewhat increased OH

production, hence a decrease in CH4 lifetime.

Thus, changes in CH4 lifetime are related in

direct and indirect ways to changes in O3 concentrations

and probably should be assessed together. The difference in estimated residence

time compared with previous 2-D studies could therefore be a result of very

different transport parameterizations in 2-D and 3-D models.

Table 4-5: Chemical lifetime (in years) of methane [columns

A, C, and E] up to 300 hPa (~10 km) and changes of this lifetime (%) (columns

B, D, and F) by including aircraft emissions (nc = not calculated).

|

|

|

| Model |

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

F

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IMAGES/BISAa |

6.60

|

-1.2%

|

6.81

|

-2.6%

|

7.36

|

-3.7%

|

| ECHAm3/CHEM |

nc

|

nc

|

6.46

|

-1.6%

|

6.51

|

-2.3%

|

| HARVARD |

9.33

|

-1.2%

|

9.43

|

-2.6%

|

nc

|

nc

|

| UiO |

8.52

|

-1.3%

|

8.59

|

-2.6%

|

9.48

|

-3.9%

|

| UKMOb |

10.52

|

-1.5%

|

10.69

|

-2.9%

|

11.26

|

-4.3%

|

| Tm3/KNMI |

8.97

|

-1.4%

|

|

-2.6%

|

|

-3.5%

|

|

|

a Uses fixed lower boundary conditions for CO.

b Lifetime up to 100 hPa; a lower lifetime is expected for integration

up to 300 hPa. |

|

Table 4-6:Relative sensitivity (%) of global ozone perturbations

from aircraft emissions.

|

Sensitivity

Case |

IMAGES/

BISA |

ECHAm3/

CHEM |

Tm3/

KNMI |

UiO |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Lightning |

|

|

|

-16 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Surface

emissions IS92a |

|

|

|

-11 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| NASA-ANCAT |

|

-20 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| NMHC chemistry |

-35 |

|

-10 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Exclusion of N2O5

removal on aerosol |

-10 |

|

0 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Interannual variability |

|

±6.3 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Scenario G - F |

|

|

|

+44 |

|

|

The reduction in CH4 lifetime would lead to a nearly uniform CH4 reduction

globally because of the relatively long residence time computed for CH4. This

result would be in contrast to O3, for which changes would occur on large regional

scales. Finally, it should be noted that for computational reasons, the experiments

in this assessment were performed using fixed CH4 concentrations at the Earth's

surface (see Section 4.2.2.1), and CH4 concentrations

at the surface were not allowed to adapt to higher OH abundances (positive feedback).

Hence, even larger CH4 decreases are to be expected if CH4 ground flux boundary

conditions are used. However, such calculations are much more computationally

intensive. IPCC (1995) and Fuglestvedt et al. (1996) showed that the feedback

factor is uncertain and model-dependent but is estimated to be in the range

1.2-1.5. Adopting a factor of 1.4 increases the percentage changes, in the CH4

lifetimes shown in Table 4-5, to -2.2 to -4.1% in

2015 and -3.2 to -6.0% in 2050. Changes in CH4 lifetime of this order will lead

to global average radiative forcing (see Chapter 6) similar

to global average radiative forcing perturbations from aircraft-induced O3 changes,

but with an opposite sign (CH4 will be reduced).

4.2.3.5. Sensitivity Studies

|

Figure 4-5: Zonally and monthly averaged change in concentration of OH (106 molecules/cm3)

and CO (%) in July as a result of emissions from aircraft in 2015, calculated by the UiO model.

|

In this section, we focus on a limited set of sensitivity studies that help

define the uncertainty range of the model calculations. Ideally, a large number

of simulations should have been performed by all the participating models. However,

only a limited number of model simulations was possible because of time constraints

and the demand of computer resources for 3-D CTM studies. Therefore, only one

or two models have performed each of the sensitivity studies. Also, some uncertainties

cannot be addressed properly. For example, modeled upper tropospheric and lower

stratospheric NOx and NOy concentrations are extremely uncertain and are difficult

to compare to measurements because of large temporal and spatial variations

and a limited number of observations (see Chapter 2).

There may be additional uncertainties from unknown processes that feed back

on increases in NOx and O3 in a future modified atmosphere.

The sensitivity studies focus on the impact on O3. The following studies were

performed:

Sensitivity of aircraft-induced O3 perturbations to background NOx levels

from lightning. This finding is obtained by increasing global average NOx

production from 5 Tg N yr-1, which is used in the reference case, to 12 Tg

N yr-1. The same spatial distribution is used in both cases.

Sensitivity of O3 perturbation to different regional growth in emissions.

In the base case (IS92a), a uniform growth rate was used for the surface emission

of pollutants. The sensitivity run was performed with the same global growth

rate as in the base case but with the different regional growth rates given

in Table 4-3.

Sensitivity to different projections of aircraft emissions. Instead of NASA

2015 emissions, the ANCAT-2015 aircraft emission data set was used. Total

ANCAT emissions for the year 2015 are about 15% larger than the NASA emissions

(see Section 9.3.4). Further differences relate to

the location and seasonal variations of emissions.

Sensitivity to inclusion of NMHC chemistry. This study was conducted by making

runs in which NMHC chemistry was excluded and comparing the results with those

in which NMHC chemistry was included.

Sensitivity to neglecting heterogeneous chemistry on background sulfate aerosols.

This sensitivity was estimated by comparing results with and without the heterogeneous

nitrogen pentoxide (N2O5) + H2O reaction on aerosol. The aerosol surface area

was derived from model calculations of the sulfur cycle. Hydrolysis of N2O5

on wet aerosol converts active NOx into the reservoir species HNO3, which

is effectively removed by rain out. Hence, in the base case, less NOy is present

in the free troposphere and LS, and emissions by aircraft are more effective

in producing O3.

Sensitivity to interannual variability in meteorology.

Sensitivity to uncertainty in emissions in 2050. This study is carried out

by using scenario G instead of scenario F from Table

4-4. Total NOx emission changes from 2 to 3.5 Tg N yr-1.

Table 4-7: Models that contributed results to this report.

|

| Model Name |

Institution |

Model Team |

| 2-D Models |

|

|

| AER |

Atmospheric and Environmental Research, Inc., USA |

Malcolm Ko, Debra Weisenstein, Courtney

Scott, Jose Rodriguez, Run-Lie Shia, N.D |

| |

|

|

| Sze |

|

|

| |

|

|

| CSIRO |

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research

Organization Telecommunications and Industrial

Physics, Australia |

Keith Ryan, Ian Plumb, Peter Vohralik,

Lakshman Randeniya |

| |

|

|

GSFC

Fleming |

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA |

Charles Jackman, David Considine, Eric |

| |

|

|

LLNL

Grant, |

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, USA |

Douglas Kinnison, Peter Connell, Keith

Douglas Rotman |

| |

|

|

| THINAIR |

University of Edinburgh, UK |

Robert Harwood, Vicky West |

| |

|

|

| UNIVAQ |

University of L'Aquila, Italy |

Giovanni Pitari, Barbara Grassi, Lucrezia

Ricciardulli, Guido Visconti |

| |

|

|

| 3-D Models |

|

|

| LARC |

NASA Langley Research Center, USA |

William Grose, Richard Eckman |

| |

|

|

| SCTM1 |

University of Oslo, Norway |

Michael Gauss, Ivar Isaksen |

| |

|

|

| SLIMCAT |

University of Cambridge, UK |

Helen Rogers, Martyn Chipperfield |

|

|

The results of the sensitivity studies are presented in Table

4-6. The table presents the relative sensitivity r (%) of each process by

comparing aircraft-induced increases in global O3 for the base case and the

sensitivity case:

| r = [(O3,2-O3,1)/O3,1]*100% |

(1) |

|

2

The model results presented in this chapter are a summary

of muchmodel output. Supplemental material regarding the effects of supersonic

aircraft are retrievable over the Internet. Supersonic model simulation

information includes figures, tables, and text and is available at a NASA

Langley Research Center computer until 31 December 2000:

Host: uadp1.larc.nasa.gov

Username: anonymous

Password: your e-mail address

Directory: IPCC_TECH_REPORTS/supersonic

Information concerning supersonic model simulations may

also be viewed (retrieved) over the Web by going to the following URL: ftp://uadp1.larc.nasa.gov/IPCC_TECH_REPORTS/supersonic/.

|

where O3,1 is the global O3 increase (kg) up to 16 km for the base case in

2015 (i.e., scenario D-C) and O3,2 is the same increase calculated for the sensitivity

study (i.e., scenario D'-C'). The sensitivity studies show that increases in

background NOx from lightning (sensitivity study 1) and different growth rates

in surface emissions in different regions (sensitivity study 2) have only a

slight impact on O3 perturbation from aircraft

emissions. In both cases, O3 perturbations are reduced. This finding shows

that O3 production in the UT and LS is limited by NOx, rather than by hydrocarbons.

Interannual variability in meteorology (sensitivity study 6) and exclusion of

heterogeneous removal of N2O5 in the models also led to a small change in global

average O3 perturbation (sensitivity study 5). Excluding hydrocarbon chemistry

(sensitivity study 4) would have a significant impact on O3, resulting in a

smaller perturbation. Furthermore, there were significant differences in the

results between the two models used to perform the study. Comparison of results

with two different emission scenarios (sensitivity study 3) showed a noticeable

impact on global O3 perturbation. Sensitivity study 7, which was set up to test

the response of O3 perturbation to greatly increased NOx emission from aircraft

(estimated upper limit in 2050), showed that the response is nearly linear and

similar to what is computed for smaller NOx perturbations.

It should be noted that the comparisons in Table 4-6

are made for global average O3 perturbations; sensitivities are larger on regional

and seasonal scales.

|